UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Table of Contents

Persepolis

Persepolis (Takht-e Jamshid) was an ancient ceremonial capital of the Persian Empire. It lies at the foot of Kuh-i-Rahmat, or “Mountain of Mercy,” in the plain of Marv Dasht about 400 miles south of the present capital city of Teheran and some 70 km northeast of the modern city of Shiraz

in the Fars Province of Iran.The largest and most complex building in Persepolis was the audience hall or Apadana with 72 columns. In contemporary Persian language the site is known as Takht-e Jamshid (Throne of Jamshid). To the ancient Persians, the city was known as Parsa, meaning The City of Persians, so Persepolis is the Greek interpretation of the mentioned name. The exact date of the founding of Persepolis is not known. It is assumed that Darius I began work on the platform and its structures between 518 and 516 B.C., visualizing Persepolis as a show place and the seat of his vast Achaemenian Empire. But its majestic audience halls and residential palaces perished in flames when Alexander conquered and looted Persepolis in 330 B.C. according to history, 20,000 mules and 5,000 camels carried away its treasures.

The first scientific excavation at Persepolis was carried out by Ernst Herzfeld in 1931, commissioned by the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. He believed the reason behind the construction of Persepolis was the need for a majestic atmosphere, as a symbol for their empire and to celebrate special events, especially the “Nowruz”, (the Persian New Year held on 21 March). For historical reasons and deep rooted interests it was built on the birthplace of the Achaemenid dynasty, although this was not the centre of their Empire at that time.

The main characteristic of Persepolitan architecture is its columns, which were made of wood. Only when even the largest cedars of Lebanon or the teak trees of India did not fulfill the required sizes did the architects resort to stone. The bases and the capitals were always of stones, even on wooden shafts, but the existence of wooden capitals is probable.

The remains including the bas-reliefs and sculptures provide an insight into hearts and beliefs of the ancient Persians. The buildings at Persepolis are divided into three areas; military quarters, the treasury and the reception and occasional houses for the King of Kings. These included the Great Stairway, the Gate of Nations (Xerxes), the Apadana palace of Darius, the Hall of a Hundred Columns, the Tripylon Hall and Tachara palace of Darius, the Hadish palace of Xerxes, the palace of Artaxerxes III, the Imperial Treasury, the Royal Stables and the Chariot house.

Gray limestone was the main material used in building Persepolis. To reach the top terrace, the construction of a broad Stairway, 20 meters above the ground, was planned to be the only main entrance. This was begun around 518 BC. The dual stairway, known as the Persepolitan stairway, was built in a symmetrical manner on the western side of the Great Wall. Originally the steps were believed to have been constructed to allow for nobles and royalty to ascend by horseback, new theories suggest that this was to allow visiting dignitaries to in fact walk up the stairs while keeping a regal appearance, permissible by the ease in which the stairs could be climbed due to the small distance between each step. Today Persepolis is still full of mystery and majesty.

Naghsh-e Jahan

Built by “Shah Abbas I the Great” at the beginning of the 17th century, and bordered on all sides by monumental buildings linked by a series of two-storied arcades, the site is known for the Royal Mosque, the Mosque of Sheykh Lotfollah, the magnificent Portico of Qaysariyyeh Bazzar.

the 15th-century Timurid palace.They are an impressive testimony to the level of social and cultural life in Persia during the Safavid era. Naghsh-e Jahan Square is surrounded by buildings from the Safavid era. “Roger Seyouri”, prominent British Iranologist who conducted extensive studies in history of Safavid era, has written that:” Naghsh-e Jahan Square was a place for citizens to visit King. All around the square there was a river and along this river a row of plane trees donated shadow to passersby’s. During the day time the square was filled with the tents of vendors and merchants stores who sold their goods, mainly spices, in warehouse around the Square. At night Naghsh-i Jahan square changed into a gathering place for actors, jugglers, puppet showers , story tellers, and mystics. Shah (King) sometimes especially in Nowruz (New Year’s Day) sat on gardens besides the Square to congratulate the beginning of new year.

All tourists who visited Isfahan in previous centuries have the same pictures from Isfahan in their mind. Fortunately physical appearance of Square remained intact and it still shows off its beauty to the world. Naghsh-e Jahan owes its glory to four sites which surrounded it from north, south, east and west and each one individually indicates a masterpiece of Iranian architecture.

Shah Mosque is standing in south side of Naghsh-e Jahan square. Built during the Safavid period, it is an excellent example of Islamic Architecture in Iran.

Its splendor is mainly because of the beauty of its seven-color mosaic tiles and valuable inscriptions. The splendid portal of the mosque measuring 27 meters high, crowned with two beautiful minarets being 42 meters in height, frames the front of the mosque which opens into Naqsh-e Jahan square. On top of the entrance, among the attractive stalactites and above the turquoise lattice windows, there is a frame of seven-color mosaic tile shaped like a vase with two peacocks on both sides which is a very precious example of mosaic tile art. The wooden door of the mosque, covered with layers of gold and silver, is ornamented with some poems written in “Nasta’liq Script”. The overall entrance hall proves the mastery of the designer of the building.

Sheikh Lotfollah mosque Situated on the eastern side of Naghsh-e Jahan Square, the mosque was constructed between 1602 to 1619 A.D. in Shah Abbas I era. It was a private praying place. According to one of the most famous American architects’: ” it is difficult to say that the Mosque is a man made building!!”

Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque in contrast with Imam Mosque is so small, because Shah Abbas constructed the mosque for one of his father in law, Sheikh Lutfullah. The mosque was named after Sheikh Lutfullah, a religious leader from Lebanon who was invited to Isfahan and was paid special attention by the Safavid king. Ali Qapu Palace was the celebrated seat of The Safavid capital in Isfahan. Ali Qapu is a pavilion that marks the entrance to the vast royal residential quarter of the Safavid Isfahan which stretched from the Maidan Naqhsh-e-Jahan to the Chahar Bagh Boulevard. The building, another wonderful Safavid edifice, was built by decree of Shah Abbas the Great in the early seventeenth century. It was here that the great monarch used to entertain noble visitors, and foreign ambassadors. Shah Abbas, here for the first time celebrated the Nowruz (New Year’s Day) of 1006 AH / 1597 A.D. A large and massive rectangular structure, the Ali Qapu is 48 meters high and has six floors, fronted with a wide terrace whose ceiling is inlaid and supported by wooden columns.

The Bazaar of Isfahan (Qeysarieh bazaar) is one of the oldest and largest bazaars of the Middle East, dating back to the 17th century A.D. The bazaar is a vaulted two kilometer street linking the old city with the new. The two kilometer bazaar is a vaulted street that links the old city, the Friday mosque and old square with Shah Abbas’ new square. The iwan of the bazaar portal is flanked by galleries and crowned with the representation of Sagittarius in mosaic tile. The portal links the royal bazaar, the royal mint, and the royal caravansary, leading to the major artery of the bazaar.

Chogha zanbil

Chogha Zanbil is the ruins of the holy city of the Kingdom of Elam, centered on a great ziggurat and surrounded by three huge concentric walls. Founded around 1250 BC, the city remained unfinished after it was invaded by Ashurbanipal in 640 BC.

Archaeological excavations between 1951 and 1962 revealed the site again, and the ziggurat is considered to be the best preserved example in the world. It is one of the few extant ziggurats outside of Mesopotamia. It was built about 1250 BCE by the king Untash-Napirisha, mainly to honor the great god Inshushinak.

The complex is protected by three concentric walls, which form three main areas of the “town.” The inner area is wholly taken up with a great ziggurat dedicated to the main god, which was built over an earlier square temple with storage rooms also built by Untash-Napirisha.

The middle area holds eleven temples for lesser gods. It is believed that twenty-two temples were originally planned, but the king died before they could be finished, and his successors discontinued the building work. In the outer area are royal palaces, a funerary palace containing five subterranean royal tombs, and a necropolis containing non-elite tombs.

Takht-e Soleyman

The archaeological site of Takht-e Soleyman (Throne of Solomon), in north-western Iran (Azarbaijan Province), is situated in a valley set in a volcanic mountain region. It lies midway between Urumieh and Hamadan, very near the present-day town of Takab, and 400 km (250 miles)

West of Tehran. The site includes the principal Zoroastrian sanctuary partly rebuilt in the Ilkhanid (Mongol) period (13th century) as well as a temple of the Sasanian period (6th and 7th centuries) dedicated to Anahita. The originally fortified site, which is located on a crater rim, was recognized as a World Heritage Site in July 2003. The citadel includes the remains of a Zoroastrian sanctuary consists of a collection of swimming pool and lake, a place of worship, entrance gates, tall columns, hall, place of swearing, fire temples, mineral hot spring, and watch towers. With its purple and blue color, the pool, known as Takht-e Soleiman Lake, is one of the wonders of this historical site. It is about 80 meters wide and 120 meters long. With a depth of 110 meters it flows like a hot spring, pumping out about 100 liters of water every second. From the southern part, the castle looks like a gate with ruined walls – the 3-roofless rooms that used to be a place of worship for ancient Iranians.

The whole area built during the Sassanid period, and partially rebuilt during the Ilkhanid period. According to legend, the temple housed one the three “Great Fires” or “Royal Fires”. Sassanid rulers are said to have journeyed there to humble themselves at the fire altar before ascending the throne.

Folk legend relates that King Solomon used to imprison monsters inside the 100 m deep crater of the nearby Zendan-e Soleyman “Prison of Solomon”. Another crater inside the fortification itself is filled with spring water; Solomon is said to have created a flowing pond that still exists today. Nevertheless, Solomon belongs to Semitic legends and therefore, the lore and namesake (Solomon’s Throne) should have been formed following Islamic conquest of Persia. After the Conquest, the Arabs sought to destroy anything Zoroastrian or Persian, as these things were deemed to be contrary to Islam.

In order to avoid this, the Persians changed the names of many sites and monuments to save them from destruction. Another example is in the city of Pasargadae, where they began referring to the tomb of Cyrus the Great as “Solomon’s mother’s tomb.” A 4th century Armenian manuscript relating to Jesus and Zarathustra, and various historians of the Islamic period, mention this pond. The foundation of the fire temple around the pond is attributed to that legend. Archaeological excavations have revealed traces of a 5th century BC occupation during the Achaemenid period, as well as later Parthian settlements in the citadel. Coins belonging to the reign of Sassanid kings, and that of the Byzantine emperor Theodosius II (AD 408-450), have also been discovered there.

The site has important symbolic significance. The designs of the fire temple, the palace and the general layout have strongly influenced the development of Islamic architecture.

Pasargadae

Pasargadae was a city in ancient Persia, and is today an archaeological site and one of Iran’s 9 UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The first capital of the Achaemenid Empire, Pasargadae, lies in ruins 43 kilometers from Persepolis, the present-day Fars province of Iran.

The construction of the capital city by Cyrus the Great, begun in 546 BCE or later, was left unfinished, for Cyrus died in battle in 530 BCE or 529 BCE. The tomb of Cyrus’ son and successor, Cambyses II, also has been found in Pasargadae. The remains of his tomb, located near the fortress of Toll-e Takht, were identified in 2006. Pasargadae remained the Persian capital until Darius founded another in Persepolis. The modern name comes from the Greek, but may derive from an earlier one used during Achaemenid times, Pâthragâda, meaning the garden of Pars. The archaeological site covers 1.6 square kilometers and includes a structure commonly believed to be the mausoleum of Cyrus, the fortress of Toll-e Takht sitting on top of a nearby hill, and the remains of two royal palaces and gardens. The gardens provide the earliest known example of the Persian famous chahar bagh, or four-fold garden design.

Latest research on Pasargadae’s structural engineering has shown the Achaemenid architectures constructed the city to withstand a severe earthquake, at what would today be classified as a ‘7.0’ on the Richter magnitude scale. The foundations are today believed as having a base isolation design, much the same as what is presently used in countries for the construction of facilities.

The most important monument in Pasargadae is the tomb of Cyrus the Great. The design of Cyrus’ Tomb is credited alternatively to Mesopotamian or Elamite ziggurats, but the cellar is usually attributed to Urartu tombs of an earlier period. In particular, the tomb at Pasargadae has almost exactly the same dimensions as the tomb of Alyattes II, father of the Lydian King Croesus; however, some have refused the claim (according to Herodotus, Croesus was spared by Cyrus during the conquest of Lydia, and became a member of Cyrus’ court). The main decoration on the tomb is a rosette design over the door within the gable. In general, the art and architecture found at Pasargadae exemplified the Persian synthesis of various traditions, drawing on precedents from Elam, Babylon, Assyria, and ancient Egypt, with the addition of some Anatolian influences.

Arg-e Bam

Being at the crossroads of important trade routes and known for the production of silk and cotton garments, Bam is situated in a desert environment on the southern edge of the Iranian high plateau. The origins of Bam can be traced back to the Achaemenid period (6th to 4th centuries BC).

But its heydays were from the 7th to 11th centuries. The existence of life in the oasis was based on the underground irrigation canals, the qanāts, of which Bam has preserved some of the earliest evidence in Iran. Arg-e Bam is the most representative example of a fortified medieval town built in vernacular technique using mud layers. The Arg-e Bam (Citadel of Bam), established in the Sassanian period, is situated atop an artificial hill in the northwest quadrant of the old city of Bam. This artificial hill elevates the citadel approximately 5 meters above the surrounding urban fabric. The citadel complex occupies an area 315 meters wide along the east-west axis by 270 meters long along the north-south axis. Bounded on the north by the river, by steep cliffs to the east, and by gardens and residential neighborhoods to the north, northwest and south, the Arg-e Bam was optimized for both self-sufficiency and protection.

This is one of the most splendid historical sites in the whole world; while most of the best known historical sites in the world signify a limited period in history, Arg-e-Bam displays the imprints of 2000 continuous years of a dramatic, eventful history .This peculiarity has made estimation of the precise age of most parts of this historical complex rather difficult, sometimes even impossible.

Security was a major concern in the Arg-e Bam; the citadel complex was surrounded by deep trenches and four encircling and dividing defensive walls. The citadel subdivided into two major sections, residential and military, separated by a wall tentatively dated to the Seljuk period. The citadel also contains three wells, located along a single north-south axis. The residential complex contains the governor’s residence, baths, a detached watchtower, the chahar fasl (four seasons) palace, the prison, the dungeons, and one of the citadel wells. The military section comprises the commander’s quarters, barracks, stables for 200 horses, and two wells. The governor’s mansion was constructed at the highest point within the Arg-e Bam, next to the complex watchtower. Heavily renovated during the Safavid (1501 – 1722) period, the mansion consists of a two-story main iwan with summer and winter wings. The prison and dungeon were located beneath the governor’s residence, rather than in the military section. This dungeon and the chahar fasl, (a specifically Iranian building type, the “four-seasons building”) are considered to be the oldest buildings within the Arg-e Bam. The detached watchtower is four-sided and decorated with shallow rectangular insets and three levels of windows. Below the watchtower platform is a chamber with an elevated entrance accessible via a staircase. The existence of other rooms within the watchtower suggests that the tower had other functions beyond that of security.

Natural disaster has recently struck Bam: shortly after the devastating earthquake of 26 December 2003, which leveled the city, the Arg-e Bam was inscribed on the 2004 World Heritage List, and added directly to the World Heritage in Danger List. Prior to the earthquake, the fortress had possessed the distinction of being the largest adobe building in the world, recognized for its unbaked mud brick and poured mud wall construction.

Soltaniy-e

Soltaniyeh situated in the Zanjan Province of Iran, some 240 km to the north-west from Tehran, used to be the capital of Ilkhanid rulers of Persia in the 14th century. Its name translates as “the Imperial”.

the Mausoleum of Il-khan Öljeitü, traditionally known as the Dome of Soltaniyeh.The structure, erected from 1302 until 1312, boasts the oldest double-shell dome in the world. Soltaniyeh is one of the outstanding examples of the achievements of Persian architecture and a key monument in the development of its Islamic architecture. The dome is the biggest in the world which is made of brick. From the elevation point of view it is the third highest of the kind in the world.

Its importance in the Muslim world may be compared to that of Brunelleschi’s cupola for the Christian architecture. The Dome of Soltaniyeh paved the way for more daring Muslim cupola constructions, such as the Mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasavi and Taj Mahal. Much of exterior decoration has been lost, but the interior retains superb mosaics, faience, and murals.

The estimated 200 ton dome stands 49 meters (161 ft) tall from its base and with 25m diameter, the dome covered in turquoise-blue faience and surrounded by eight slender minarets .The whole building was completed in 10 years, but the 200 ton dome building takes only 40 days, while whole of this huge structure is founded on 50cm foundation.

Pope has described the building as “anticipating the Taj Mahal.”

Armenian Monastic Ensembles

The Armenian Church and Monastery of St. Thaddeus, locally called Qara Kelisa (the Black Church) is situated in desolate, but nowadays easily accessible, country about 18 km south of Maku. Northwest Iran is home to the oldest churches in the country among which Qara Kelisa, St.

Stephanos, and Zoorzoor stand out because of their antiquity. The St. Thaddeus Church is considered one of the oldest churches in the world, whose construction began 1700 years ago. Historians believe that the Church is the tomb of St. Thaddeus who is said to have been one of Christ’s disciples who traveled to Armenia, then part of the Persian Empire, for preaching the teachings of Christ. Armenians followed Thaddeus’ teachings and converted to Christianity in 301 AD. St.Thaddeus was later martyred and buried in the present-day West Azarbaijan province. A tomb was erected on his burial place by his followers who turned it into a small prayer house. The building was later changed into a cathedral in the seventh century AD. According to the inscriptions remained there, the Church was ruined in by a devastating earthquake but was later restored in its current form by a Christian religious figure. Today the church belongs to the Armenian community of Iran. It has an international reputation and hosts annual meetings of world Armenians each year in July-August. The present cruciform building, said to be on the site of this early church, stands on a hill within fortified walls and consists of two distinct parts: a domed sanctuary end built largely of dark stone, probably dating from the tenth or eleventh century, and the main body of the church, built of light sandstone, under a second and larger tent dome whose twelve-sided drum is pierced by an equal number of windows.

According to an inscription dating 1329 this latter section was rebuilt after an earthquake in 1319; considerable additions were, however, made during the 19th century, possibly when there was an abortive move to transfer here from Echmiadzin in present Armenia the seat of Armenian Catholics. The exterior walls are, like those of other early Armenian churches, decorated with bas-reliefs, the effigies of saints and a lively frieze of vine leaves and animals on the newer building being particularly striking. Ruined buildings within a walled compound adjoining the western fortified walls indicate that a considerable monastic settlement once existed there. The church has one service a year, on the feast day of St. Thaddeus (around 19 June), when Armenian pilgrims from all over Iran camp for three days to attend the ceremonies.

Because of special features, antiquity, architectural style, decorations, its religious importance among the world Armenians, and the celebrations held annually in Qara Kelisa, Iran’s Armenian Monastic Ensembles have been designated as one of the country’s sites to be inscribed onto the UNESCO’s World Heritage List.

Sheikhsafi al-Din

The Sheikh Safi al-Din Khanegah and Shrine Ensemble in Ardabil is a Sufi spiritual retreat dating from between the early 16th century and late 18th century. It is the burial site of Safi al-Din Ardabili

(B. 1252/3), the eponymous founder of the Safawiyya order of Sufism. The complex is a fine example of medieval Iranian architecture.

The shrine was an important site of pilgrimage throughout the Safavid period (1501-1722) and underwent numerous improvements and embellishments to become one of the most beautiful of all Safavid monuments.

The site includes a library, a mosque, a school, a mausoleum, a cistern, a hospital, kitchens, a bakery and some offices. The floor of the shrine is covered with a reproduction of the most famous carpet in the world – the Ardebil Carpet.

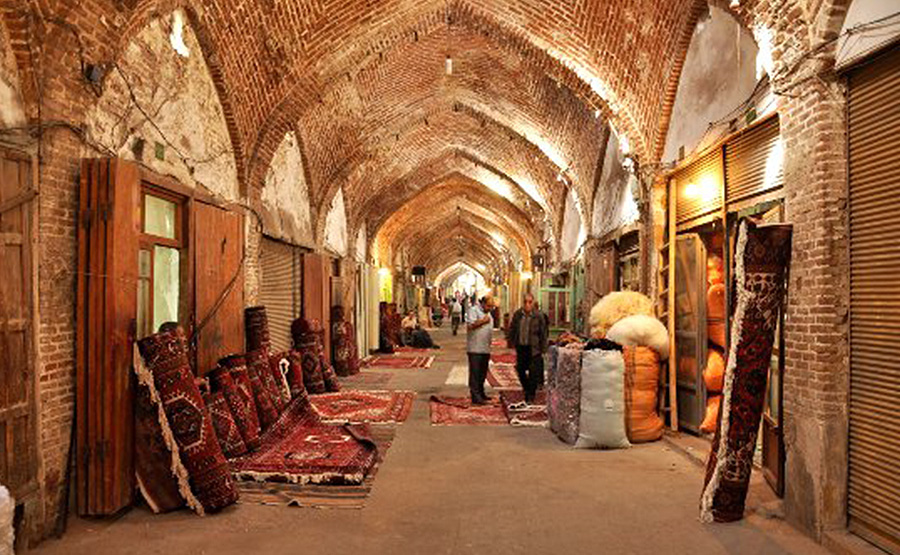

Tabriz Bazaar

The Tabriz Historic Bazaar Complex is one of the oldest bazaars of the Middle East and the largest covered bazaar in the world. Tabriz has been a place of cultural exchange since antiquity and its historic bazaar complex is one of the most important commercial centers on the Silk Road.

The most prosperous time of Tabriz and its complex Bazaar was in the 13th century when town became the capital city of Safavid kingdom. The city lost its status as capital in the 16th century, but its Bazaar has remained important as a commercial and economic center.

Bisotun

Bisotun is an archaeological site located along a historical trade route in the Kermanshah Province of Iran, containing remains dating from pre-historic times through the history of ancient Persia. Its bears unique testimony to the Persian Empire and the interchange of influences in art and writing in the region.

Its primary monument is the Bisotun Inscription, made in 521 BC by Darius I the Great when he conquered the Persian throne. The inscription is written in 3 languages: Elamite, Babylonian and Old Persian. It is to cuneiform script what the Rosetta stone is to Egyptian hieroglyphs: the document most crucial in the decipherment of a previously lost script. A British army officer, Sir Henry Rawlinson, had the inscription transcribed in two parts, in 1835 and 1843.

Shushtar

Shushtar, Historical Hydraulic System, is an island city from the Sassanian era with a complex irrigation system.

The river was channeled to form a moat around the city, while bridges and main gates into Shushtar were built to the east, west, and south. Several rivers nearby are conducive to the extension of agriculture; the cultivation of sugar cane, the main crop, dates back to 226 CE. A system of subterranean channels called Ghanats, which connected the river to the private reservoirs of houses and buildings, supplied water for domestic use and irrigation, as well as to store and supply water during times of war when the main gates were closed. Traces of these ghanats can still be found in the crypts of some houses. This complex system of irrigation degenerated during the 19th century.

Persian Garden

The Persian Garden” comprises nine gardens from different epochs and climates. They derive from the Chahar Bagh model, which dates back to the 6th Century BC.

The designated gardens are:

– Pasargadae

– Bagh-e Eram

– Bagh-e Chehel Sotun

– Bagh-e Fin

– Bagh-e Dolat Abad

– Bagh-e Pahlavanpur

– Bagh-e Shahzadeh

– Bagh-e Abas Abad

– Bagh-e Akbariyeh

Masjed-e Jāmé of Isfahan

Located in the historic centre of Isfahan, the Masjed-e Jāmé (‘Friday mosque’) can be seen as a stunning illustration of the evolution of mosque architecture over twelve centuries, starting in ad 841. It is the oldest preserved edifice of its type in Iran and a prototype for later mosque designs throughout Central Asia. The complex, covering more than 20,000 m2, is also the first Islamic building that adapted the four-courtyard layout of Sassanid palaces to Islamic religious architecture. Its double-shelled ribbed domes represent an architectural innovation that inspired builders throughout the region. The site also features remarkable decorative details representative of stylistic developments over more than a thousand years of Islamic art.

Gonbad-e Qābus

The 53 m high tomb built in ad 1006 for Qābus Ibn Voshmgir, Ziyarid ruler and literati, near the ruins of the ancient city of Jorjan in north-east Iran, bears testimony to the cultural exchange between Central Asian nomads and the ancient civilization of Iran. The tower is the only remaining evidence of Jorjan, a former centre of arts and science that was destroyed during the Mongols’ invasion in the 14th and 15th centuries. It is an outstanding and technologically innovative example of Islamic architecture that influenced sacral building in Iran, Anatolia and Central Asia. Built of unglazed fired bricks, the monument’s intricate geometric forms constitute a tapering cylinder with a diameter of 17–15.5 m, topped by a conical brick roof. It illustrates the development of mathematics and science in the Muslim world at the turn of the first millennium AD.

Visible from great distances in the surrounding lowlands near the ancient Ziyarid capital, Jorjan, the 53-metre high Gonbad-e Qābus tower dominates the town laid out around its base in the early 20th century. The tower’s hollow cylindrical shaft of unglazed fired brick tapers up from an intricate geometric plan in the form of a ten pointed star to a conical roof. Two encircling Kufic inscriptions commemorate Qābus Ibn Voshmgir, Ziyarid ruler and literati as its founder in 1006 AD.

The tower is an outstanding example of early Islamic innovative structural design based on geometric formulae which achieved great height in load-bearing brickwork. Its conical roofed form became a prototype for tomb towers and other commemorative towers in the region, representing an architectural cultural exchange between the Central Asian nomads and ancient Iranian civilisation.

Golestan Palace

The lavish Golestan Palace is a masterpiece of the Qajar era, embodying the successful integration of earlier Persian crafts and architecture with Western influences. The walled Palace, one of the oldest groups of buildings in Teheran, became the seat of government of the Qajar family, which came into power in 1779 and made Teheran the capital of the country. Built around a garden featuring pools as well as planted areas, the Palace’s most characteristic features and rich ornaments date from the 19th century. It became a centre of Qajari arts and architecture of which it is an outstanding example and has remained a source of inspiration for Iranian artists and architects to this day. It represents a new style incorporating traditional Persian arts and crafts and elements of 18th century architecture and technology.

Golestan Palace is located in the heart and historic core of Tehran. The palace complex is one of the oldest in Tehran, originally built during the Safavid dynasty in the historic walled city. Following extensions and additions, it received its most characteristic features in the 19th century, when the palace complex was selected as the royal residence and seat of power by the Qajar ruling family. At present, Golestan Palace complex consists of eight key palace structures mostly used as museums and the eponymous gardens, a green shared centre of the complex, surrounded by an outer wall with gates.

The complex exemplifies architectural and artistic achievements of the Qajar era including the introduction of European motifs and styles into Persian arts. It was not only used as the governing base of the Qajari Kings but also functioned as a recreational and residential compound and a centre of artistic production in the 19th century. Through the latter activity, it became the source and centre of Qajari arts and architecture.

Golestan Palace represents a unique and rich testimony of the architectural language and decorative art during the Qajar era represented mostly in the legacy of Naser ed-Din Shah. It reflects artistic inspirations of European origin as the earliest representations of synthesized European and Persian style, which became so characteristic of Iranian art and architecture in the late 19th and 20th centuries. As such, parts of the palace complex can be seen as the origins of the modern Iranian artistic movement.

Shahr-i Sokhta

Shahr-i Sokhta, meaning ‘Burnt City’, is located at the junction of Bronze Age trade routes crossing the Iranian plateau. The remains of the mudbrick city represent the emergence of the first complex societies in eastern Iran. Founded around 3200 BC, it was populated during four main periods up to 1800 BC, during which time there developed several distinct areas within the city: those where monuments were built, and separate quarters for housing, burial and manufacture. Diversions in water courses and climate change led to the eventual abandonment of the city in the early second millennium. The structures, burial grounds and large number of significant artefacts unearthed there, and their well-preserved state due to the dry desert climate, make this site a rich source of information regarding the emergence of complex societies and contacts between them in the third millennium BC.

Located at the junction of Bronze Age trade routes crossing the Iranian plateau, the remains of the mud brick city of Shahr-i Sokhta bear witness to the emergence of the first complex societies in eastern Iran. Founded around 3200 BCE, the city was populated during four main periods up to 1800 BCE, during which time there developed several distinct areas within the city. These include a monumental area, residential areas, industrial zones and a graveyard.

Changes in water courses and climate change led to the eventual abandonment of the city in the early second millennium. The structures, burial grounds and large number of significant artefacts unearthed there and their well-preserved state due to the dry desert climate make this site a rich source of information regarding the emergence of complex societies and contacts between them in the third millennium BCE.

Cultural Landscape of Maymand

Maymand is a self-contained, semi-arid area at the end of a valley at the southern extremity of Iran’s central mountains. The villagers are semi-nomadic agro-pastoralists. They raise their animals on mountain pastures, living in temporary settlements in spring and autumn. During the winter months they live lower down the valley in cave dwellings carved out of the soft rock (kamar), an unusual form of housing in a dry, desert environment. This cultural landscape is an example of a system that appears to have been more widespread in the past and involves the movement of people rather than animals.

Maymand is a small and relatively self-contained south facing valley within the arid chain of Iran’s central mountains. The villagers are agro-pastoralists who practice a highly specific three phase regional variation of transhumance that reflects the dry desert environment. During the year, farmers move with their animals to defined settlements, traditionally four, and more recently three, that include fortified cave dwellings for the winter months. In three of these settlements the houses are temporary, while in the fourth, the troglodytic houses are permanent.

Susa

Located in the south-west of Iran, in the lower Zagros Mountains, the property encompasses a group of archaeological mounds rising on the eastern side of the Shavur River, as well as Ardeshir’s palace, on the opposite bank of the river. The excavated architectural monuments include administrative, residential and palatial structures. Susa contains several layers of superimposed urban settlements in a continuous succession from the late 5th millennium BCE until the 13th century CE. The site bears exceptional testimony to the Elamite, Persian and Parthian cultural traditions, which have largely disappeared.

Located in the lower Zagros Mountains, in the Susiana plains between the Karkheh and Dez Rivers, Susa comprises a group of artificial archaeological mounds rising on the eastern side of the Shavur River, encompassing large excavated areas, as well as the remains of Artaxerxes’ palace on the other side of the Shavur River. Susa developed as early as the late 5th millennium BCE as an important centre, presumably with religious importance, to soon become a commercial, administrative and political hub that enjoyed different cultural influences thanks to its strategic position along ancient trade routes. Archaeological research can trace in Susa the most complete series of data on the passage of the region from prehistory to history

The Persian Qanat

Throughout the arid regions of Iran, agricultural and permanent settlements are supported by the ancient qanat system of tapping alluvial aquifers at the heads of valleys and conducting the water along underground tunnels by gravity, often over many kilometres. The eleven qanats representing this system include rest areas for workers, water reservoirs and watermills. The traditional communal management system still in place allows equitable and sustainable water sharing and distribution. The qanats provide exceptional testimony to cultural traditions and civilizations in desert areas with an arid climate.

Maymand is a small and relatively self-contained south facing valley within the arid chain of Iran’s central mountains. The villagers are agro-pastoralists who practice a highly specific three phase regional variation of transhumance that reflects the dry desert environment. During the year, farmers move with their animals to defined settlements, traditionally four, and more recently three, that include fortified cave dwellings for the winter months. In three of these settlements the houses are temporary, while in the fourth, the troglodytic houses are permanent.

Historic City of Yazd

The City of Yazd is located in the middle of the Iranian plateau, 270 km southeast of Isfahan, close to the Spice and Silk Roads. It bears living testimony to the use of limited resources for survival in the desert. Water is supplied to the city through a qanat system developed to draw underground water. The earthen architecture of Yazd has escaped the modernization that destroyed many traditional earthen towns, retaining its traditional districts, the qanat system, traditional houses, bazars, hammams, mosques, synagogues, Zoroastrian temples and the historic garden of Dolat-abad.

The City of Yazd is located in the deserts of Iran close to the Spice and Silk Roads. It is a living testimony to intelligent use of limited available resources in the desert for survival. Water is brought to the city by the qanat system. Each district of the city is built on a qanat and has a communal centre. Buildings are built of earth. The use of earth in buildings includes walls, and roofs by the construction of vaults and domes. Houses are built with courtyards below ground level, serving underground areas. Wind-catchers, courtyards, and thick earthen walls create a pleasant microclimate. Partially covered alleyways together with streets, public squares and courtyards contribute to a pleasant urban quality. The city escaped the modernization trends that destroyed many traditional earthen cities. It survives today with its traditional districts, the qanat system, traditional houses, bazars, hammams, water cisterns, mosques, synagogues, Zoroastrian temples and the historic garden of Dolat-abad. The city enjoys the peaceful coexistence of three religions: Islam, Judaism and Zoroastrianism.

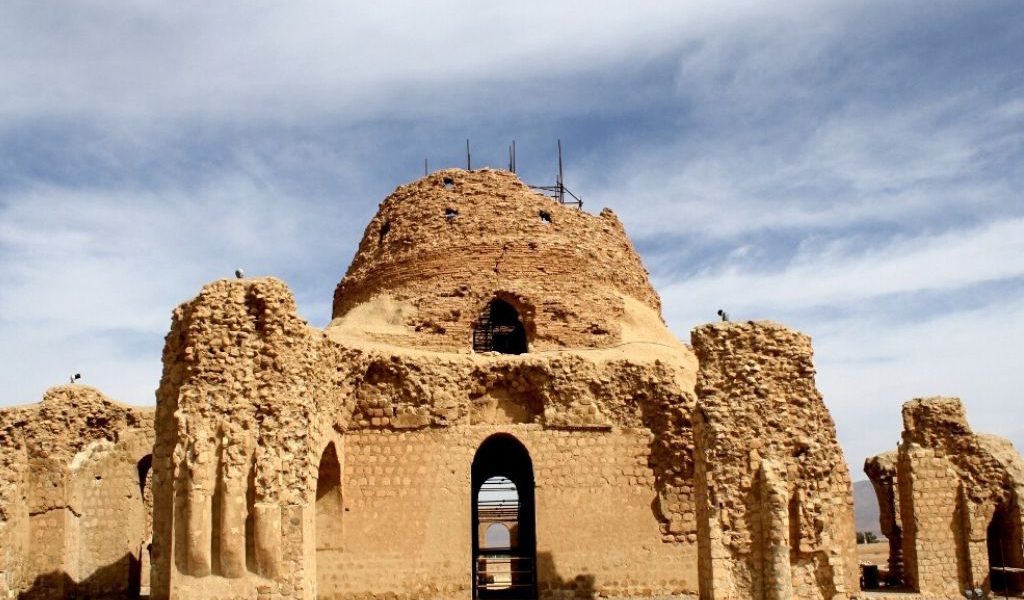

Sassanid Archaeological Landscape of Fars Region

The eight archaeological sites situated in three geographical areas in the southeast of Fars Province: Firuzabad, Bishapur and Sarvestan. The fortified structures, palaces and city plans date back to the earliest and latest times of the Sassanian Empire, which stretched across the region from 224 to 658 CE. Among these sites is the capital built by the founder of the dynasty, Ardashir Papakan, as well as a city and architectural structures of his successor, Shapur I. The archaeological landscape reflects the optimized utilization of natural topography and bears witness to the influence of Achaemenid and Parthian cultural traditions and of Roman art, which had a significant impact on the architecture of the Islamic era.

The serial property Sassanid Archaeological Landscape of the Fars Region is composed of 8 selected archaeological site components in three geographical area contexts at Firuzabad, Bishapur and Sarvestan, all located in the Fars Province of southern Iran. The components include fortification structures, palaces, reliefs and city remains dating back to the earliest and latest moments of the Sassanid Empire, which stretched across the region from 224 to 651 CE. Among the sites are the dynasty founder Ardashir Papakan’s military headquarters and first capital, and a city and architectural structures of his successor, the ruler Shapur I. In Sarvestan, a monument dating into the Early Islamic period illustrates the transition from the Sassanid to the Islamic era.

The ancient cities of Ardashir Khurreh and Bishapur include the most significant remaining testimonies of the earliest moments of the Sassanid Empire, the commencement under Ardashir I and the establishment of power under both Ardashir I and his successor Shapur I. In locations strategically selected for defence purposes, the cities were planned in their surrounding environments and illustrate urban typologies, such as the circular shape of Ardashir Khurreh, which became influential to later Sassanid and Islamic cities. The surrounding landscape was imprinted with Sassanid testimonies, such as the reliefs and sculptures cut into the rock cliffs and the defensive structures protecting the cities. The architecture of the Sassanid monuments in the property further illustrates early examples of construction of domes with squinches on square spaces, such as in the chahar-taq buildings, where the four sides of the square room show arched openings: this architectural form turned into the most typical form of Sassanid religious architecture, relating closely to the expansion and stabilization of Zoroastrianism under Sassanid reign and continuing during the Islamic era thanks to its usage in religious and holy buildings such as mosques and tombs.

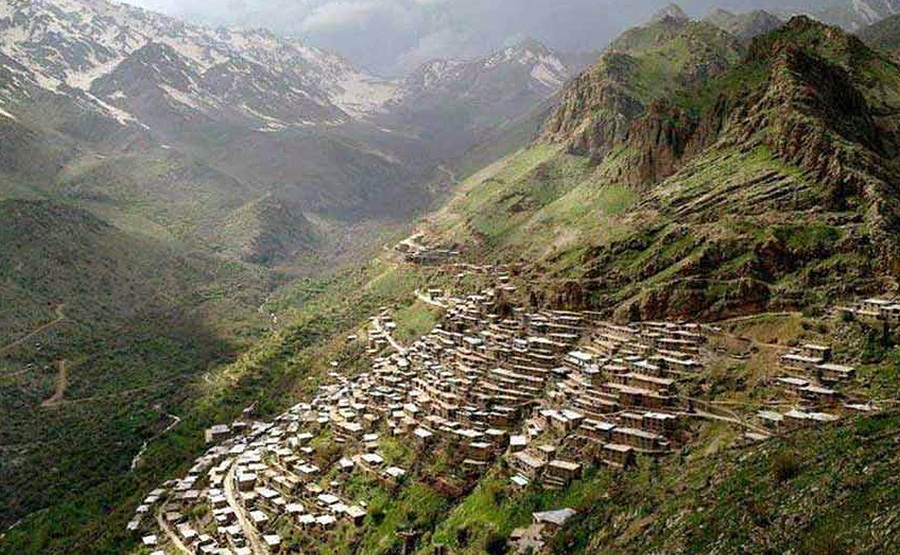

Cultural Landscape of Hawraman/Uramanat

The remote and mountainous landscape of Hawraman/Uramanat bears testimony to the traditional culture of the Hawrami people, an agropastoral Kurdish tribe that has inhabited the region since about 3000 BCE. The property, at the heart of the Zagros Mountains in the provinces of Kurdistan and Kermanshah along the western border of Iran, encompasses two components: the Central-Eastern Valley (Zhaverud and Takht, in Kurdistan Province); and the Western Valley (Lahun, in Kermanshah Province). The mode of human habitation in these two valleys has been adapted over millennia to the rough mountainous environment. Tiered steep-slope planning and architecture, gardening on dry-stone terraces, livestock breeding, and seasonal vertical migration are among the distinctive features of the local culture and life of the semi-nomadic Hawrami people who dwell in lowlands and highlands during different seasons of each year. Their uninterrupted presence in the landscape, which is also characterized by exceptional biodiversity and endemism, is evidenced by stone tools, caves and rock shelters, mounds, remnants of permanent and temporary settlement sites, and workshops, cemeteries, roads, villages, castles, and more. The 12 villages included in the property illustrate the Hawrami people’s evolving responses to the scarcity of productive land in their mountainous environment through the millennia.

The Cultural Landscape of Hawraman/Uramanat is located at the heart of the Zagros Mountains in the provinces of Kurdistan and Kermanshah along the western border of Iran. It is comprised of two component parts: the Central-Eastern Valley (Zhaverud and Takht, in Kurdistan Province); and the Western Valley (Lahun, in Kermanshah Province). The mode of human habitation in these areas has been adapted over millennia to the rough mountainous environment.

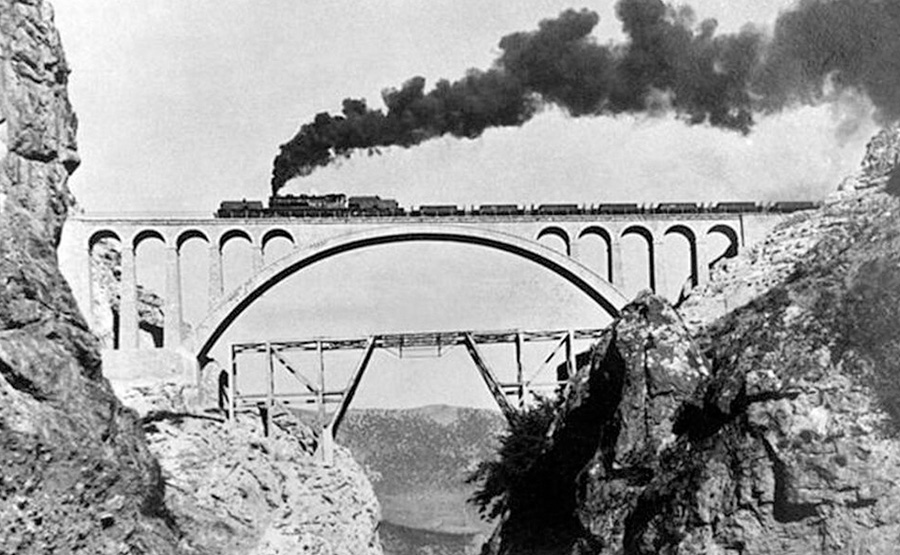

Trans-Iranian Railway

The Trans-Iranian Railway connects the Caspian Sea in the northeast with the Persian Gulf in the southwest crossing two mountain ranges as well as rivers, highlands, forests and plains, and four different climatic areas. Started in 1927 and completed in 1938, the 1,394-kilometre-long railway was designed and executed in a successful collaboration between the Iranian government and 43 construction contractors from many countries. The railway is notable for its scale and the engineering works it required to overcome steep routes and other difficulties. Its construction involved extensive mountain cutting in some areas, while the rugged terrain in others dictated the construction of 174 large bridges, 186 small bridges and 224 tunnels, including 11 spiral tunnels. Unlike most early railway projects, construction of the Trans-Iranian Railway was funded by national taxes to avoid foreign investment and control.

Lut Desert

The Lut Desert, or Dasht-e-Lut, is located in the south-east of the country. Between June and October, this arid subtropical area is swept by strong winds, which transport sediment and cause aeolian erosion on a colossal scale. Consequently, the site presents some of the most spectacular examples of aeolian yardang landforms (massive corrugated ridges). It also contains extensive stony deserts and dune fields. The property represents an exceptional example of ongoing geological processes.

The Lut Desert is in the southeast of the Islamic Republic of Iran, an arid continental subtropical area notable for a rich variety of spectacular desert landforms. At 2,278,015 ha the area is large and is surrounded by a buffer zone of 1,794,134 ha. In the Persian language ‘Lut’ refers to bare land without water and devoid of vegetation. The property is situated in an interior basin surrounded by mountains, so it is in a rain shadow and, coupled with high temperatures, the climate is hyper-arid. The region often experiences Earth’s highest land surface temperatures: a temperature of 70.7°C has been recorded within the property.

Hyrcanian Forests

Hyrcanian forests form a unique forested massif that stretches 850 km along the southern coast of the Caspian Sea. The history of these broad-leaved forests dates back 25 to 50 million years, when they covered most of this Northern Temperate region. These ancient forest areas retreated during the Quaternary glaciations and then expanded again as the climate became milder. Their floristic biodiversity is remarkable: 44% of the vascular plants known in Iran are found in the Hyrcanian region, which only covers 7% of the country. To date, 180 species of birds typical of broad-leaved temperate forests and 58 mammal species have been recorded, including the iconic Persian Leopard (Panthera pardus tulliana).

The Hyrcanian Forests form a green arc of forest, separated from the Caucasus to the west and from semi-desert areas to the east: a unique forested massif that extends from south-eastern Azerbaijan eastwards to the Golestan Province, in Iran. The Hyrcanian Forests World Heritage property is situated in Iran, within the Caspian Hyrcanian mixed forests ecoregion. It stretches 850 km along the southern coast of the Caspian Sea and covers around 7 % of the remaining Hyrcanian forests in Iran.

The property is a serial site with 15 component parts shared across three Provinces (Gilan, Mazandaran and Golestan) and represents examples of the various stages and features of Hyrcanian forest ecosystems. Most of the ecological characteristics which characterize the Caspian Hyrcanian mixed forests are represented in the property. A considerable part of the property is in inaccessible steep terrain. The property contains exceptional and ancient broad-leaved forests which were formerly much more extensive however, retreated during periods of glaciation and later expanded under milder climatic conditions. Due to this isolation, the property hosts many relict, endangered, and regionally and locally endemic species of flora, contributing to the high ecological value of the property and the Hyrcanian region in general.